Curvism instead cubism — The neuroscience of curved spaces.

The Curvist Theory: 10,000 Years of Human Geometry Trauma

Why our ancestors thrived in curved environments, how hard angles reshaped the nervous system, and why your body still remembers the geometry of home.

For most of human history, humans lived inside curves — caves, huts, yurts, tipis, circular villages. Geometry was not aesthetic; it was biological. In the last 10,000 years, fortifications, grids and rigid planning pushed humanity into boxes and 90º corners.

The Curvist Theory asks a simple, uncomfortable question: What happens to a curved nervous system when it is forced to live in straight cages?

Geometry as Nervous System Diet

Curvist Theory proposes that geometry functions like a long-term diet for the nervous system. Sharp intersections, narrow corridors and repetitive rectangular rooms generate chronic micro-stress, vigilance and perceptual fatigue.

This is not metaphor. It is biology interacting with space.

Cross-Cultural Evidence: 43 Civilizations, One Pattern

Long before neuroscience or environmental psychology, cultures across the planet — isolated by geography and time — independently associated sharp corners, rigid angles and enclosed rectangular spaces with discomfort, danger or spiritual disturbance. This is not myth. It is pattern recognition.

Scroll horizontally and vertically to explore the table.

| Culture | Name of the Negative Energy | How They Discovered These Were Evil Spaces | Cleansing Practices |

|---|---|---|---|

| Feng Shui (China) | Sha Qi (煞气) (cutting or harmful energy) | They noticed that sharp corners and dark areas caused discomfort, conflicts, or illnesses. | Mirrors, plants, lighting, moving water. |

| Taoism (China) | "Gui" (ghosts or stagnant energy) | They observed that cluttered spaces or those full of objects attracted wandering souls or blocked the flow of "Qi". | Bells, incense, talismans (such as peach wood swords), furniture arrangement to harmonize the "Qi". |

| Tibetan Buddhism | "Drekpa" (spiritual contamination in corners) | Monks noticed that dark or neglected corners in gompas or rectangular houses attracted lesser spirits, causing disturbances or illness. | Burning juniper incense in the corners, reciting mantras (e.g., "Om Mani Padme Hum"), placing prayer flags. |

| Xiongnu (northern steppes, Russia) | "Qutugh" (spiritual corruption, approximate term) | While inhabiting captured Chinese settlements, shamans noticed that dark or poorly ventilated corners attracted evil spirits or "air diseases". | Chants and drumming directed at the corners, sprinkling water with ashes, avoiding storing objects in corners. |

| Kipchaks/Cumans (Russian and Ukrainian steppes) | "Yaman ruhlar" (evil spirits in Turkish) | In occupied Russian churches and houses, they felt that corners retained spirits or hostile energies, linked to bad luck or illness. | Burning dried dung or herbs, protective stones, rituals with bows and arrows. |

| Mongols | "Trapped evil spirits" or "Buyan-iin khüch" (corrupt force) | While conquering sedentary regions, they observed that corners accumulated heavy energies or restless spirits, causing illness or discord. | Juniper or mugwort smoke, drumming, offerings of milk or vodka in the corners. |

| Sarmatians (Russian and Caspian steppes) | "Dark forces at the edges" (inferred term) | In captured settlements or Roman fortifications, they perceived corners as accumulators of shadows or stagnant energies. | Burning herbs (sage), metal or bone amulets, fire rituals. |

| Sami (Scandinavia and Russia) | "Stallo" or trapped spirits | Their conical lavvus felt free; colonial rectangular houses felt oppressive and retained evil spirits. | Yoik chants, reindeer offerings in the corners. |

| Alans | "Arwah-i bad" (evil spirits, approximate term) | While occupying Byzantine or Russian rectangular houses, they noticed that dark corners generated oppression or illness. | Burning herbs (sage or juniper), chants or drumming, amulets in the corners. |

| Pechenegs | "Kara Ruhlar" (dark spirits) | In Russian or Byzantine rectangular houses, they observed that corners accumulated dead energies or hostile spirits. | Burning dung or herbs, symbolic bows and arrows, chants to Tengri, offerings of milk or vodka. |

| Scythians (Russian and Ukrainian steppes) | "Wandering souls in angles" | They noticed that Greek rectangular houses trapped spirits of the dead or hostile forces. | Animal sacrifices (horses), sprinkling blood or milk in the corners. |

| Khazars | "Stagnant spirits" or "Kötü Ruhlar" | While occupying conquered cities, they noticed that corners caused discomfort or negative events. | (Not specified in this version; suggested: chants, smoke). |

| Vastu Shastra (India) | Vastu Dosha (energy imbalance) | They observed that certain house designs brought misfortune and health problems. | Sacred fire (Havan), yantras, reorientation of furniture, specific colors. |

| Thai Culture (Theravada Buddhism) | "Phi Tai Hong" (vengeful spirits in corners) | Monks and villagers observed that dark corners accumulated spirits of violent deaths. | Offerings of food or flowers, Buddhist sutras, amulets. |

| Shintoism (Japan) | Kimon (鬼門, "Demon Gate") | They identified specific directions (northeast) as prone to negative spirits. | Purification with water (Misogi), sakaki branches, offerings at shrines. |

| Ainu (Japan/Russia) | "Evil Kamui" | Traditional houses had no right angles; modern Japanese houses felt disruptive. | Prayers to Kamuy, cleansing with willow branches. |

| Zoroastrianism (Ancient Persia) | "Druj" (impurity or corruption) | They believed that dirty or stagnant corners could be inhabited by daevas. | Sacred fire, cleansing with pure water, exposure to sunlight. |

| European Geomancy | Evil nodes and ley lines | They noticed that certain places were prone to illnesses and accidents. | Protective symbols, salt, relocating buildings. |

| Inuit (American Arctic, Greenland, Russia) | "Spirits trapped in angles" | Corners blocked the flow of spirits, causing oppression or poor hunting. | Throat singing, amulets, ventilation. |

| Cherokee (North America) | Stagnant energy in corners | Dark corners caused discomfort or visions, unlike rounded houses. | Sacred tobacco, chants, keeping corners clean. |

| Navajo (North America) | "Chindi" (trapped spirits of the dead) | Their circular hogans were free; colonial rectangular houses accumulated chindi. | Burning cedar, chants to expel spirits. |

| Andean Shamanism | Jucha (heavy energy) | They believed that enclosed and dark places accumulated negative spirits. | Smoking with herbs, drum and conch sounds. |

| Shipibo-Conibo (Amazon) | Yacuruna in corners | Corners accumulated heavy, damp energies linked to evil spirits. | Icaros, palo santo, clearing corners. |

| Mapuche (Southern Cone, Argentina and Chile) | Wekufe in angles | Machi noticed that in rectangular houses, corners accumulated sticky energies. | Kultrun drums, smoking with canelo, avoiding storage in corners. |

| Mexica (Mesoamerica) | "Mictlan in corners" (underworld influence) | In temples and homes, dark corners attracted energies from Mictlan. | Burning copal, ritual sweeping, offerings (flowers or jade). |

| Maya Culture | "Xibalba" (underworld influence) | Dark corners or misaligned buildings were connected to the underworld. | Burning copal, offerings of blood or food, altars. |

| Celtic Tradition | Shadowy places or "broken spaces" | They avoided sites with bad energetic sensations. | Consecrated water, fire, stone circles. |

| Hoodoo/Voodoo (African American) | Crossroads energy (trapped energy) | They believed that corners and crossroads attracted wandering entities. | Protective powders, chalk symbols, prayers, oils. |

| Islamic Beliefs | Jinn in dark corners | They said Jinn inhabited dirty and poorly ventilated spaces. | Recitation of the Quran, holy water (Zamzam), incense. |

| Bedouins (Middle East) | Jinn in corners | Curved tents allowed spiritual flow; rectangular houses trapped jinn. | Reciting Quran verses, salt in corners. |

| Ancient Egypt | "Isfet" (chaos or energetic disorder) | They believed that misaligned spaces attracted chaotic forces opposed to "Maat". | Incense (myrrh or kyphi), alignment with cardinal points, Nile water. |

| Yoruba Culture (West Africa) | "Ajogun" (destructive forces) | Neglected corners were seen as portals for hostile entities. | Offerings to Orishas, herbs (basil), drums. |

| Zulu Culture (Southern Africa) | "Angry Amadlozi" (disturbed ancestors) | In colonial houses, corners trapped ancestral energy, causing disharmony. | Burning imphepho, chants, water with ashes. |

| Dogon Culture (Mali) | "Unbalanced Nommo" (stagnant spiritual energy) | In rectangular houses, corners accumulated heavy energy. | Mud markings, millet offerings, ritual dances. |

| Akan Culture (Ghana) | "Sasa" (vengeful spirits in corners) | They noticed that corners attracted unappeased spirits. | Palm wine libations, protective herbs, ritual stools. |

| Berber Culture (North Africa) | "Jnun in corners" (evil spirits) | In kasbahs and rectangular houses, dark corners were inhabited by Jnuns. | Myrrh or amber incense, protective verses, salt. |

| Khoisan (Southern Africa) | "Restless spirits in corners" | Temporary curved shelters; colonial houses were linked to illnesses and disharmony. | Trance dances, herbal smoke. |

| Swahili Culture (East Africa) | "Shetani" (demons in corners) | In rectangular stone houses, corners accumulated shadows that attracted demons. | Holy water, coral or wooden amulets, Islamic prayers. |

| Mesopotamian Culture (Sumerians, Babylonians) | "Evil spirits" or "Utukku" | They observed that houses with shadowy areas were prone to possessions and misfortune. | Rituals with salt, protective figurines (apkallu), incantations. |

| Australian Aboriginals | Trapped spirits | When interacting with colonial cubic houses, they noticed that corners accumulated bad vibrations. | Eucalyptus smoke, chants, avoiding sleeping near corners. |

| Polynesians, Māori (New Zealand) | "Kehua in corners" (restless spirits) | In European rectangular houses, dark corners trapped spirits. | "Karakia" prayers, spring water, kawakawa branches. |

| Melanesians (Papua New Guinea) | "Masalai in straight edges" | With colonial cubic buildings, corners attracted territorial spirits. | Burning herbs, protective carvings, avoiding right angles. |

| Micronesians (Caroline Islands) | "Stagnant Aniti" | In adopted rectangular structures, corners accumulated dead energies. | Chants, salt water, shells as protectors. |

The Amazonian Connection

During Federico Garcia’s life in Venezuela, he frequently interacted with aboriginal tribes in the southern regions of the country. Some of these communities lived near the Amazon basin, while others were located beyond it, yet shared strikingly similar cultural and spatial patterns.

For those who have had the privilege of engaging with these societies, one observation stands out clearly: despite profound cultural differences, these communities exhibit remarkable emotional stability, coherence of reasoning, and psychological resilience. This is not anecdotal romanticism, but a consistent qualitative pattern that invites a deeper question—what role does their living environment play in mental well-being?

One of the most revealing aspects lies in their architecture. Many of these tribes inhabit circular dwellings that integrate seamlessly with their surroundings. These structures are not merely aesthetic; they reflect an implicit logic of optimisation. Circular forms minimise material usage, maximise ergonomic efficiency, and create spatial continuity that feels instinctively welcoming.

When compared to rigid, angular constructions, an unavoidable question emerges: what value is gained by building environments that disrupt ergonomic balance and environmental harmony at their core?

“Trapped within rigid, square structures, we unknowingly sever our natural connection with organic environments.”

Behavioral and psychological metrics suggest that deep down, humans instinctively recognize this misalignment, but generations of conditioning have led us to suppress these insights. By analyzing spatial patterns and the psychological impacts of confinement, it becomes evident that only by breaking free from these geometric constraints can we truly experience the restorative potential of biophilia, reconnecting with the organic flow essential to human well-being.

Unconsciously, we detect the detriments imposed by these environments, but years of normalized conditioning compel us to cling to the perceived security of cubic forms. These environments, often revered for their practicality, impose finite boundaries and sharp angles that inadvertently contribute to emotional and mental strain. Data trends and psychometric studies consistently reveal that such confined spaces amplify stress responses and suppress cognitive flexibility. Despite this understanding, we persist in perpetuating a spatial paradigm that distances us from nature and authentic freedom.

This phenomenon, based on historical metrics and environmental patterns, has been unfolding over the last six to seven thousand years. Evidence suggests that humanity has willingly confined itself within cubic enclosures for millennia, gradually diminishing our connection to the natural world. This disconnect, once measured and contextualized, offers a compelling case for rethinking our architectural frameworks and realigning them with the organic principles that support human harmony.”

But we shouldn’t feel guilty. We’ve all been trapped in this, and it’s easy to overlook the long-term consequences when they’ve become so normal. It’s not that we didn’t know—it’s more that we allowed ourselves to forget, ignoring the harm of these cubic confinements until now.

Many people feel comfortable within these environments, their nervous systems conditioned from birth—often from their very first breath in the cubic geometry of a hospital room. Having known nothing else, the cycle simply continues.

How can we recognise an illness if we have never experienced health long enough to contrast it? Without a reference point, dysfunction dissolves into familiarity.

This is the reality we, the so-called “civilised,” inhabit: environments that slowly erode our well-being while disguising harm as normality. We have distanced ourselves from what a truly healthy, natural existence feels like.

That is the reality we, the so-called ‘civilised,’ are living. Trapped in environments that slowly erode our well-being, unable to fully recognise the depth of the harm because we’ve never known anything different. We’ve distanced ourselves from what a truly healthy, natural existence feels like.”

Venezuelan writer Gustavo Pereira captures this contrast with piercing irony when describing cultures untouched by angular domination:

🛖 “The Pemones of La Gran Sabana call the morning dew: Chiriyé Yetaku, which means Saliva of the stars. To tears, Emú Parapué, which translates to guarapo of the eyes (soft coffee). They call the heart: Yewán Enapué, the seed of the womb. Another tribe from the Orinoco River Delta, the Warao, say Mejokoji, the Sun of the chest, to name the Soul. To say friend, they say Ma Jokaraisa: My other heart. And to say forget, Emonikitane, which means: forgive. The very fools do not know what they are saying. To say land, they say mother. To say mother, they say tenderness. To say tenderness, they say delivery. They are so confused in their feelings that, of course, we good people rightly call them SAVAGES.”

The irony is unmistakable. Those we label “savages” live embedded in nature, their language reflecting an intimate understanding of life, emotion, and connection. Meanwhile, we—entombed in angular structures—mistake rigidity for progress, unaware that it steadily distances us from what truly matters.

The Samsara Discovery

From an epistemological constructivist perspective, knowledge is not a direct mirror of reality but an active construction shaped by cultural, social, and historical conditions. Values, beliefs, and collective practices influence how societies perceive nature over time. Consequently, our relationship with the natural environment is neither objective nor universal—it is learned, reinforced, and normalised across generations.

This insight is central to understanding how humanity gradually accepted rigid, angular environments as “normal,” despite their biological and psychological costs.

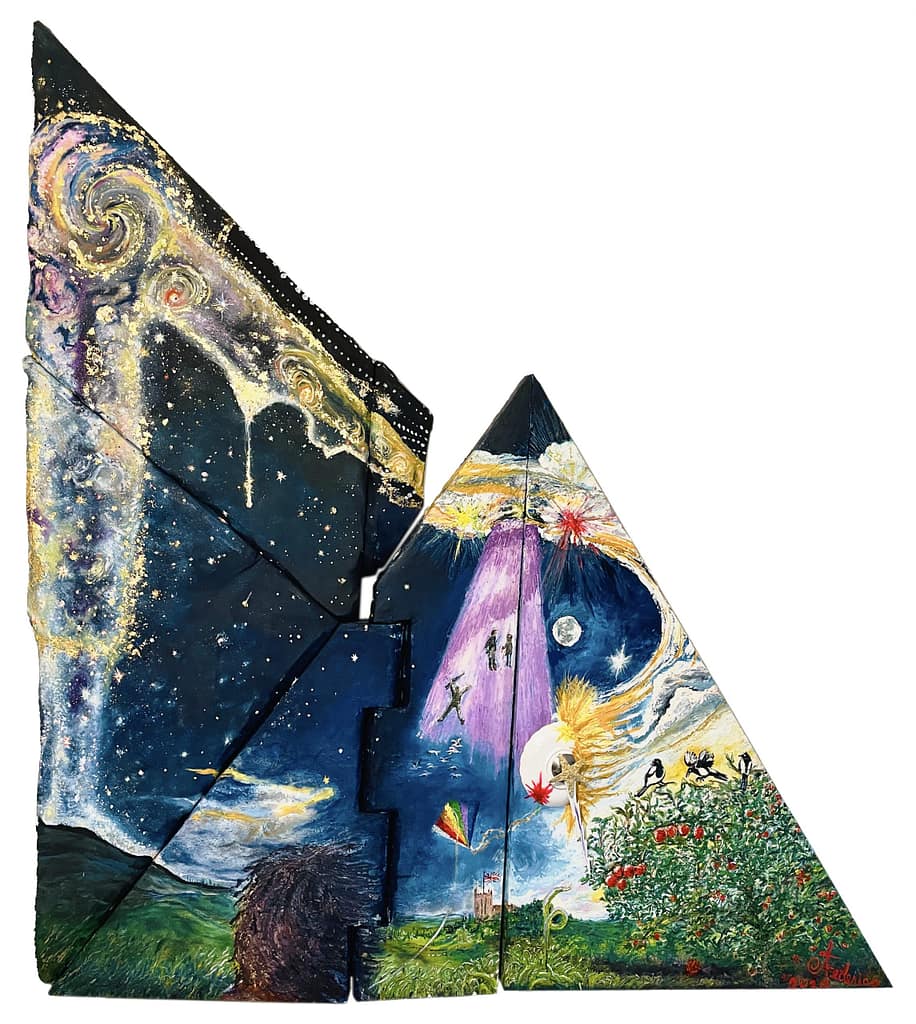

In his recent artistic project (2023–2024), Federico García explored this process through an educational board game that connects human evolutionary history with Buddhist cosmology. The project draws a parallel between the major eras of human development—Neolithic Age, Metal Age, Classical Antiquity, Middle Ages, Modern Age, and Contemporary Age—and the realms of the Wheel of Samsara described in Buddhist texts: Hell, Hungry Ghosts, Animals, Humans, Demigods, and Gods.

These realms represent six recurring states of experience within a closed cycle, while a seventh perspective—outside the wheel—is indicated by Buddha pointing toward the moon: a symbolic invitation to liberation beyond repetitive suffering.

García highlights that Buddhist teachings, far from being purely spiritual abstractions, offer practical insights into human development at both individual and civilisational scales. The analogy between Samsara and historical ages suggests that societies, like individuals, evolve through repeating patterns of desire, fear, power, and identity.

Within this framework, the Realm of Humans occupies a unique position. It balances pleasure, suffering, distraction, and awareness—making liberation possible, but never guaranteed. This balance mirrors the contemporary condition: unprecedented technological power paired with deep psychological disorientation.

Viewed through this lens, architecture becomes more than shelter; it becomes an evolutionary interface. The architecture of the Seventh Age—the Contemporary Age—demands re-evaluation. Defined by quantum technologies and complex systems, this era exposes the limits of rigid, mechanistic design philosophies inherited from earlier ages of control and domination.

In parallel, the psychoanalyst Erich Fromm, in Psychoanalysis of Contemporary Society, proposed that societies can be analysed much like individuals. He argued that modern social systems—particularly under industrial capitalism—produce what he called the “pathology of normality”: conditions where widespread psychological dysfunction is mistaken for health simply because it is socially shared.

Fromm’s insight is crucial here. When environments systematically alienate individuals from nature, from each other, and from themselves, distress becomes invisible through normalisation. Architecture, in this sense, is not neutral—it silently participates in shaping collective mental states.

Together, these perspectives suggest that humanity’s long residence within rigid geometric environments is not merely a technical or aesthetic choice, but a cultural condition reinforced over centuries. Understanding this conditioning is a necessary step toward designing spaces aligned with human biology, perception, and the possibility of liberation—both psychological and societal.

The Metal Age Revelation

Historical data reveals a clear and consistent pattern beginning with the Metal Age. As humanity learned to forge metals, it also began minting coins, manufacturing weapons, consolidating armies, and constructing empires. This shift marked a profound transformation in social organisation, power dynamics, and territorial control.

Alongside these developments emerged a parallel architectural revolution.

The strategic need to govern, defend, and administer growing populations required spaces that could be easily measured, replicated, surveilled, and controlled. Housing and urban layouts gradually evolved toward rigid, rectilinear forms—structures optimized not for human biology, but for efficiency, order, and dominance.

Euclidean geometry became the structural language of power.

Straight lines, right angles, grids, and cubic enclosures offered predictability and standardisation. They simplified construction, facilitated military logistics, and reinforced hierarchical organisation. As a result, these forms became the foundation of early cities and later civilizations, embedding control into the very geometry of daily life.

What began as a functional response to technological and military demands slowly solidified into a cultural norm. Over centuries, rigid architectural forms ceased to be perceived as instruments of control and instead became synonymous with progress, safety, and civilisation itself.

However, this historical alignment between geometry and power raises a critical question:

If these structures were designed primarily to manage territories and populations, what long-term cost did they impose on the human nervous system, cognition, and emotional regulation?

The Metal Age did not merely reshape tools and economies—it reshaped the environments in which human perception evolved. Understanding this shift is essential to evaluating the cumulative psychological and biological consequences of living for millennia inside architectures born from domination rather than human-centred design.

Trapped in the Illusion – An ancient army frozen inside a golden cube, symbolizing the rigid structures of civilization and the illusion of power. Curvism challenges these geometric prisons, inviting us to break free and reclaim our natural flow.”

The Neuroscience Evidence

What once appeared to be a functional architectural solution now reveals a hidden and accumulating cost. Contemporary neuroscience is increasingly uncovering how long-term exposure to rigid geometric patterns negatively impacts mental health, emotional regulation, and collective well-being. This historical analysis not only links architectural form to power structures, but also opens a critical debate about the cumulative effects of living for millennia inside spaces shaped by the geometry of domination.

As Henri Poincaré observed in Space and Geometry:

“Geometry does not deal with natural solid bodies, but with ideal bodies, absolutely invariable. These ideal bodies are complete inventions of our spirit, and experience only allows us to extract them.”

As societies advanced technologically, so did our architectural tools and the structures we inhabit. Data from modern neuroscience now highlights the impact of these forms, detached from nature, on our mental health and well-being. Studies show that environments dominated by rigid geometric patterns, such as cubes and straight lines, increase cortisol levels, a biomarker for stress, while natural and fractal designs reduce it significantly (Joye & Van Den Berg, 2010; Coburn et al., 2019).

Today, we are at an exciting technological threshold that allows us to recognize the benefits of returning to nature. However, the cumulative human cost of living more than 6,000 years in the cubic cages of Euclidean geometry, dating back to the Metal Age, has yet to be fully assessed. This architectural model, functional for its time, no longer aligns with our current physiological and spiritual needs. For instance, evidence suggests that urban environments with high Euclidean density correlate with increased rates of anxiety and depression (Berman et al., 2012).

We are currently at a technological and scientific threshold that allows us to objectively measure these effects. However, the cumulative human cost of more than 6,000 years living inside Euclidean, cubic architectures, dating back to the Metal Age, has yet to be fully quantified. What was once functionally necessary no longer aligns with our contemporary physiological, cognitive, or even spiritual needs. Empirical evidence suggests that urban environments with high Euclidean density correlate strongly with increased rates of anxiety and depression (Berman et al., 2012).

Research in political ecology and environmental psychology further demonstrates that human relationships with nature are culturally constructed. Different societies interpret the same landscape in radically different ways: one may experience a forest as sacred, another as a purely economic resource. When these cultural relationships are ignored in urban planning, environments are produced that actively disrupt our innate biophilic tendencies, increasing long-term cognitive and psychological strain.

Within this context, neuroarchitecture emerges as a critical multidisciplinary field. Promoted by the Academy of Neuroscience for Architecture (Sternberg & Wilson, 2006), neuroarchitecture integrates architectural practice with neuroscience and psychology, using experimental data to study how spatial perception affects emotion, cognition, and decision-making (Mallgrave, 2009; Pallasmaa et al., 2013).

Brain imaging studies provide compelling evidence: curved and organic designs activate the anterior cingulate cortex, associated with positive emotional responses and cognitive flexibility, while sharp, angular forms consistently stimulate the amygdala, a brain region linked to threat detection and stress responses (Vartanian et al., 2013).

As Barbara Tversky aptly states:

“Little by little, the importance of spatial thinking—reasoning with the body acting in space and the things we create in the world—is being recognized. Spatial thinking is the foundation of thought. Not the whole tower, but the foundation.”

This recognition underscores the profound influence spatial design has not only on individual cognition, but on collective behaviour and societal health. Yet, as Tversky implies, this foundational layer of human thought has been largely neglected in architectural models driven by industrial efficiency rather than human-centred design.

Despite extensive evidence supporting Biophilic Theory, our adaptation to cubic environments remains deeply entrenched. As a result, the full physical, cognitive, and psychological consequences of these environments remain under-measured. This gap raises urgent questions:

What physiological toll has accumulated from generations living in Euclidean cities?

Urban populations show up to a 40% higher prevalence of stress-related disorders compared to rural populations (Peen et al., 2010).

How much cognitive potential has been suppressed by square environments?

Research on children’s spatial reasoning links exposure to natural environments with enhanced creativity and problem-solving abilities (Kuo & Sullivan, 2001).

What are the economic costs of treating illnesses exacerbated by these environments?

Governments worldwide allocate billions annually to healthcare costs associated with urban stress syndromes.

Together, these findings suggest that architectural geometry is not a neutral backdrop, but an active agent shaping human health, cognition, and behaviour—often in ways we are only beginning to understand.

The Way Forward Is the Curvist Path

The Spanish naturalist Joaquín Araujo captures this moment of transition with striking clarity:

“We must change to face change, and change always costs. We must overcome models that fragment and simplify the ecological and social framework… It is not possible to change life without changing life.”

This call for transformation resonates deeply with contemporary movements such as biophilia and neuroarchitecture, which argue that urban environments must be redesigned to align with our innate physiological and psychological needs. The challenge is no longer whether change is necessary, but whether we are willing to reassess the models we have normalised for centuries.

From a Curvist perspective, the cost of maintaining current urban and architectural paradigms far exceeds the investment required to redesign spaces around human well-being. The evidence is no longer speculative; it is measurable.

Key Findings on Neuroperceptual Processing and Natural Complexity

Environments incorporating fractal geometry reduce mental fatigue by up to 60% compared to rigid, non-organic designs.

Exposure to natural patterns improves memory retention by approximately 14% (Coburn et al., 2019).

These findings suggest that the human brain is not merely comforted by nature—it is cognitively optimised by it.

Implications of Biophilic Design

Integrating curved edges and organic elements into built environments has been shown to reduce stress and improve mental health at scale.

Architectural use of fractal patterns enhances creativity, emotional stability, and perceptual fluency (Kardan et al., 2015).

As García’s work demonstrates, the fusion of neuroscience and art is not decorative—it is functional. Curvism proposes a shift from architecture as containment toward architecture as biological support system.

By rejecting the limitations of Euclidean rigidity and embracing biophilic principles, it becomes possible to envision a new era of urban design—one that restores continuity between human biology, perception, and the spaces we inhabit.

This is not a return to the past.

It is a recovery of an intelligence we never lost, only suppressed.

🔬 The Curvist Lab — Tools & Metrics

Want to see the numbers and the tools I created to measure how much you lose or fail to gain when you live trapped inside rectangular spaces? Enter the Curvist Lab and explore the real metrics behind geometric stress.

🔍 Visit The Curvist LabStart measuring the real economic, emotional and cognitive impact of cubic living.

The Curvism Framework

The Three Pillars of Curvism

Pillar 1 — Curvism Manifesto

Defines what Curvism is: its philosophy, principles, and why curves are essential to human wellbeing and biophilic design.

Pillar 2 — 10,000 Years of Geometry Trauma

• 🔴 You are here.

This page explains what happened to us as a species when we moved from organic, curved habitats into rigid rectangular systems.

It traces the last 10,000 years of geometric trauma — how straight lines, corners, and grids reshaped our cities,

our behavior, and our nervous system.

This is not history for architects — it is history written into the body.

Continue to Pillar 3 →

Pillar 3 — Spatial Archetypes

Demonstrates that the body and psyche always knew the truth: architecture speaks directly to the unconscious through form.