The Amazonian Connection

During Federico Garcia’s life in Venezuela, he frequently interacted with aboriginal tribes in the southern regions of the country. Some of these tribes were located near the Amazon basin, while others were outside this region but shared similar cultural and structural characteristics. For those who have had the privilege of engaging with these communities, the qualitative and observational data collected reveal a remarkable sense of emotional stability and coherence in their reasoning, despite the significant cultural differences that may exist between us. This insight provides a measurable framework for understanding the interplay between their living environments and mental well-being.

One of the most notable aspects observed is the architectural harmony of the circular homes that many of these tribes inhabit. These structures not only align aesthetically with their surroundings but also demonstrate a natural optimisation of resources. Circular designs, found across civilisations and geographies since ancient times, appear to be driven by a logical algorithm of efficiency, minimising material usage while maximising ergonomic comfort and creating an inviting environment. When benchmarked against rigid, angular designs, it raises a critical question: What value lies in constructing something that inherently disrupts an adequate ergonomic or environmental equilibrium?

“Trapped within rigid, square structures, we unknowingly sever our natural connection with organic environments. Behavioral and psychological metrics suggest that deep down, humans instinctively recognize this misalignment, but generations of conditioning have led us to suppress these insights. By analyzing spatial patterns and the psychological impacts of confinement, it becomes evident that only by breaking free from these geometric constraints can we truly experience the restorative potential of biophilia, reconnecting with the organic flow essential to human well-being.

Unconsciously, we detect the detriments imposed by these environments, but years of normalized conditioning compel us to cling to the perceived security of cubic forms. These environments, often revered for their practicality, impose finite boundaries and sharp angles that inadvertently contribute to emotional and mental strain. Data trends and psychometric studies consistently reveal that such confined spaces amplify stress responses and suppress cognitive flexibility. Despite this understanding, we persist in perpetuating a spatial paradigm that distances us from nature and authentic freedom.

This phenomenon, based on historical metrics and environmental patterns, has been unfolding over the last six to seven thousand years. Evidence suggests that humanity has willingly confined itself within cubic enclosures for millennia, gradually diminishing our connection to the natural world. This disconnect, once measured and contextualized, offers a compelling case for rethinking our architectural frameworks and realigning them with the organic principles that support human harmony.”

But we shouldn’t feel guilty. We’ve all been trapped in this, and it’s easy to overlook the long-term consequences when they’ve become so normal. It’s not that we didn’t know—it’s more that we allowed ourselves to forget, ignoring the harm of these cubic confinements until now.

Many people still feel comfortable, their minds conditioned from birth, with their amygdala hyper-activated from their first breath in the cubic room of a hospital. It’s no surprise; they’ve known nothing else, and so the cycle continues.

How can we understand the illness we’re experiencing if we’ve never had the chance to contrast it with a healthy environment for long enough? Without that point of reference, the sickness fades into the background, blending into what we’ve always known.

That is the reality we, the so-called ‘civilised,’ are living. Trapped in environments that slowly erode our well-being, unable to fully recognise the depth of the harm because we’ve never known anything different. We’ve distanced ourselves from what a truly healthy, natural existence feels like.”

Venezuelan writer Gustavo Pereira ironically describes with great accuracy a reality that contrasts with our own, the reality of those who live free from angular forms:

🛖 “The Pemones of La Gran Sabana call the morning dew: Chiriyé Yetaku, which means Saliva of the stars. To tears, Emú Parapué, which translates to guarapo of the eyes (soft coffee). They call the heart: Yewán Enapué, the seed of the womb. Another tribe from the Orinoco River Delta, the Warao, say Mejokoji, the Sun of the chest, to name the Soul. To say friend, they say Ma Jokaraisa: My other heart. And to say forget, Emonikitane, which means: forgive. The very fools do not know what they are saying. To say land, they say mother. To say mother, they say tenderness. To say tenderness, they say delivery. They are so confused in their feelings that, of course, we good people rightly call them SAVAGES.”

This poem, with its ironic tone, exposes the disconnection that we, the ‘civilized,’ have suffered. Those we call ‘savages’ live in harmony with nature; their words reflect a deep understanding of what it truly means to be connected to the natural world. Meanwhile, we, trapped in our cubic prisons, have lost that connection, believing that our angular forms are progress, when in fact they distance us from what really matters.”

The Samsara Discovery

From an epistemological constructivist perspective, knowledge is not a direct representation of reality but an active construction influenced by the cultural and social context. This position suggests that values, beliefs and social practices shape how we perceive nature over time. Thus, our perceptions of the natural environment are neither objective nor universal but products of social and historical interactions.

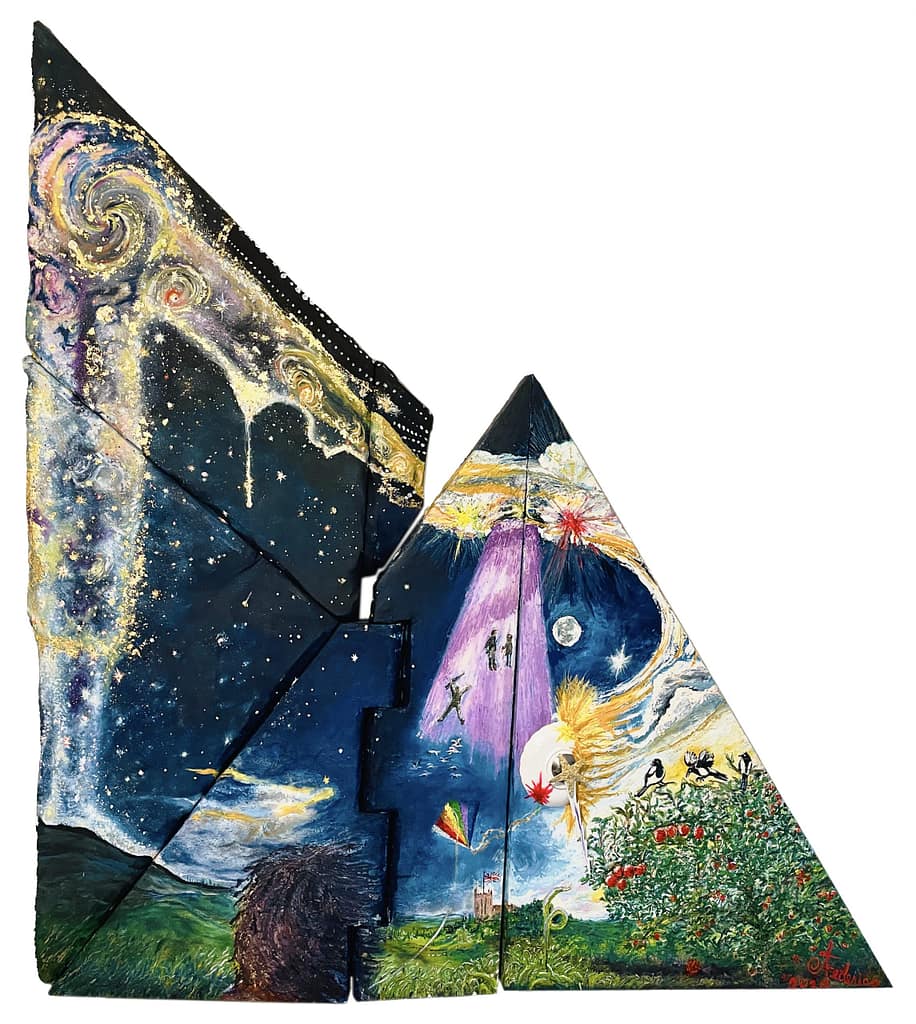

In his latest artistic project (2023/2024), Federico García developed a series of illustrations for a board game designed for educational and recreational purposes. In this project, he compared the seven great eras of human evolution (Neolithic Age, Metal Age, Classical Antiquity, Middle Ages, Modern Age, and Contemporary Age) with the realms of the Wheel of Samsara described in Buddhist texts: the Realm of Hell, Hungry Ghosts, Animals, Humans, Demigods, and Gods. These realms comprise six levels of experience within the wheel, with a seventh level observed outside of it, as pointed out by Buddha, who shows the moon and invites us to consider the path to liberation beyond this endless cycle of suffering.

García emphasizes that Buddha’s teachings on how to achieve a full life contain practical insights into the large-scale understanding of human evolution. The analogies between Samsara and human ages also apply to spiritual growth levels. According to this perspective, the Wheel of Samsara explains how liberation is possible in all realms, although the adverse circumstances in each realm present significant challenges. However, the Realm of Humans offers a unique balance between worldly distractions, suffering, and pleasures that, when mastered, allows individuals to transcend suffering.

The connection between thousands of years of scientific history and Buddhist spirituality can provide stronger reasons to approach the architecture of the Seventh Age—the Contemporary Age—defined by quantum possibilities. In this age, we not only see God in everything around us but also suspect, in our deepest intimacy, that the eyes reading these words are God’s very own.

In his book Psychoanalysis of Contemporary Society, Erich Fromm draws an analogy between society and an individual, suggesting that modern societies can be evaluated similarly to a person’s mental health. Fromm analyzes how social systems, especially capitalism, profoundly influence human character, generating what he calls the “pathology of normality,” where social norms alienate and distort psychological well-being. This perspective highlights how societal structures, far from being healthy, can foster disconnection from oneself and others.

The Metal Age Revelation

A Historical Discovery Through Data Analysis:

Since the Metal Age, historical data reveals a clear pattern: humanity, as it began forging coins and weapons, consolidated armies and eventually built empires. This evolution in control and power not only transformed social dynamics but also marked the beginning of an architectural revolution. The strategic need to organize and protect populations drove the creation of rigid housing structures, designed to reinforce control and defense. These structures, based on Euclidean geometry, became the cornerstone of emerging cities and civilizations.

The Neuroscience Evidence

However, what once seemed like a functional solution now reveals a hidden cost: recent research in modern neuroscience is uncovering how this reliance on rigid geometric patterns has negatively impacted our mental health and collective well-being. This historical analysis not only connects architectural designs to power dynamics but also sparks a debate about the cumulative effects of living for millennia in spaces shaped by the geometry of domination.

As Henri Poincaré noted in his work Space and Geometry:

“Geometry does not deal with natural solid bodies, but with ideal bodies, absolutely invariable. These ideal bodies are complete inventions of our spirit, and experience only allows us to extract them.”

As societies advanced technologically, so did our architectural tools and the structures we inhabit. Data from modern neuroscience now highlights the impact of these forms, detached from nature, on our mental health and well-being. Studies show that environments dominated by rigid geometric patterns, such as cubes and straight lines, increase cortisol levels, a biomarker for stress, while natural and fractal designs reduce it significantly (Joye & Van Den Berg, 2010; Coburn et al., 2019).

Today, we are at an exciting technological threshold that allows us to recognize the benefits of returning to nature. However, the cumulative human cost of living more than 6,000 years in the cubic cages of Euclidean geometry, dating back to the Metal Age, has yet to be fully assessed. This architectural model, functional for its time, no longer aligns with our current physiological and spiritual needs. For instance, evidence suggests that urban environments with high Euclidean density correlate with increased rates of anxiety and depression (Berman et al., 2012).

In political ecology and environmental studies, researchers examine how different social groups interact with their environments according to their cultural constructs. For instance, one culture may see a forest as a sacred space, while another may view it solely as a source of economic value. These cultural differences highlight how deeply societal circumstances shape our relationships with nature. When these relationships are neglected in urban planning, the resulting environments can disrupt our innate biophilic tendencies, increasing the cognitive and psychological toll on individuals.

In this context, neuroarchitecture emerges as a multidisciplinary approach, promoted by the Academy of Neuroscience for Architecture (Sternberg & Wilson, 2006). This field integrates architectural practice with scientific methods, using experimental data to understand how environmental perceptions affect our emotions, cognitive abilities, and decision-making (Francis Mallgrave, 2009; Pallasmaa et al., 2013). For example, brain imaging studies have shown that curved, natural designs activate the anterior cingulate cortex, associated with positive emotional responses, whereas sharp, angular forms stimulate the amygdala, linked to stress responses (Vartanian et al., 2013).

As Barbara Tversky notes:

“Little by little, the importance of spatial thinking, reasoning with the body acting in space and the things we create in the world, is being recognized... Spatial thinking is the foundation of thought. Not the whole tower, but the foundation.”

This recognition highlights the potential of spatial design to profoundly impact not only individual cognition but also societal behaviour. Yet, as Tversky suggests, this foundational aspect of human thought has been marginally addressed in architectural practices dominated by industrial efficiency over human-centred design.

Many studies confirm the positive impact of applying Biophilic Theory, emphasizing natural elements in design. Despite this, our adaptation to cubic buildings remains so entrenched that we have yet to measure the full extent of their physical, cognitive, and psychological consequences. This oversight raises critical questions:

What physiological toll has accumulated from generations of living in Euclidean cities?

Studies indicate a 40% higher prevalence of stress-related disorders in urban areas compared to rural ones. (Peen et al., 2010).

How much cognitive potential has been hindered by square structures?

Research on children’s spatial reasoning links naturalistic environments to enhanced problem-solving and creativity (Kuo & Sullivan, 2001).

What are the economic implications of treating illnesses exacerbated by these environments?

Governments worldwide allocate billions annually to healthcare costs associated with urban stress syndromes.

The Way Forward Is the Curvist Path

The Spanish naturalist Joaquín Araujo captures this need for change:

“We must change to face change, and change always costs. We must overcome models that fragment and simplify the ecological and social framework… It is not possible to change life without changing life.”

This call for transformation aligns with contemporary movements such as biophilia and neuroarchitecture, which advocate for urban environments that resonate with our innate spiritual and physiological needs. García argues that the cost of maintaining current urban models far exceeds the investment required to reimagine our cities through designs that prioritize human well-being.

Key Findings on Neuroperceptual Processing and Natural Complexity:

Environments with fractal geometry reduce mental fatigue by 60% compared to rigid designs.

Natural patterns improve memory retention by up to 14% (Coburn et al., 2019).

Implications of Biophilic Design:

Integrating curved edges and natural elements into urban spaces can reduce stress and improve mental health on a large scale.

Incorporating fractal patterns in architecture has been shown to enhance creativity and emotional stability (Kardan et al., 2015).

As García’s designs demonstrate, the fusion of neuroscience and art offers a path toward architectural liberation. By embracing biophilic principles and rejecting the limitations of Euclidean rigidity, we can envision a new era of urban design that fosters connection with nature and nurtures human potential.

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window) WhatsApp